The Super Bowl's real origin story

A reprise of posts from my study into the coverage of Super Bowl I

Vince Lombardi stood in his makeshift office inside one of the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum’s locker rooms. He had just coached the Green Bay Packers to a 35-10 victory over the Kansas City Chiefs in the first AFL-NFL World Championship Game, a contest the media had dubbed the “Super Bowl.”

A throng of newspaper reporters with their notepads, TV and radio broadcasters with their lights, cameras and microphones crowded into the room to interview Lombardi, who was holding the game ball his players had presented to him after the victory. The questions started coming about how good the Chiefs – the champions of the upstart American Football League – compared with the other teams in the established National Football League, the league the Packers represented

“Kansas City is a good football team,” Lombardi said, “But their team doesn’t compare with the top National Football League teams. I think Dallas is a better football team.” There was silence in the office, except for the reporters’ scribbling. Lombardi added, “that’s what you’ve wanted me to say, now I’ve said it.”

Lombardi’s quote about the Chiefs would be featured on the front pages of sport sections across the country, in some instances in headlines. In a game that was hyped as the meeting between two teams and two leagues, Lombardi’s proclamation was taken as the final judgment.

The Super Bowl has become, by any measure, not just the biggest sporting event in the United States but also a touchstone event in the country’s pop culture calendar. Super Bowl LIX will be one of the most watched TV shows in broadcast history, and thousands of media credentials have been issued for the game.1

One interesting part of the Super Bowl’s mythology is its growth from humble, modest origins to the center of the sports and cultural world. Famously, the first game was officially called the AFL-NFL World Championship Game – the name Super Bowl didn’t officially get tagged to the game until the third one. The Packers-Chiefs game was the only Super Bowl that did not sell out.

Reporters looking back at the game years ago recalled a lack of hype. Will McDonough, the longtime football reporter for the Boston Globe, remembered that “They issued just 328 media credentials then. (In 1991) it’s over 2,000 and they turned away 1,000.” Jerry Greene of The Detroit News remembered more bluntly, “There was no hoopla.”

The Super Bowl mythology is best encapsulated by Pat Summerall, the former New York Giants kicker and longtime football broadcaster: “There was none of the hype that we now associate with the game; in fact, nobody really wanted to play the game.”

In fact, the game story was on the front page of The New York Times the day after. Not the sports section. The front page of The Times. 1-A, above the fold. A photo of Lombardi accepting the trophy from commissioner Pete Rozelle was the lead photo of that day’s paper of record.

Origin stories fascinate me.

They’re often used not to tell listeners or readers how something started but rather build a mythology around the thing itself, or the founders of it. This is how you get the almost cliche of tech companies beginning in someone’s garage. One researcher told This American Life:

It's like, no one wants to hear the story of the rich, well-connected guys who meet up at the Marriott conference room to hatch a business plan. There's no romance in that.

One of my first research projects in graduate school examined the Super Bowl’s origin story. I wanted to know if that origin story of humble beginnings was true or not. I love a good historical debunking, where the story that we tell about an event or a person isn’t quite true.

This week’s essay comes from a series of posts from the original Sports Media Guy from the late 2010s that I repurposed here in 2023. Since a lot of you are relatively new, I figured you might like my nerdy deep dive into coverage of the first Super Bowl.

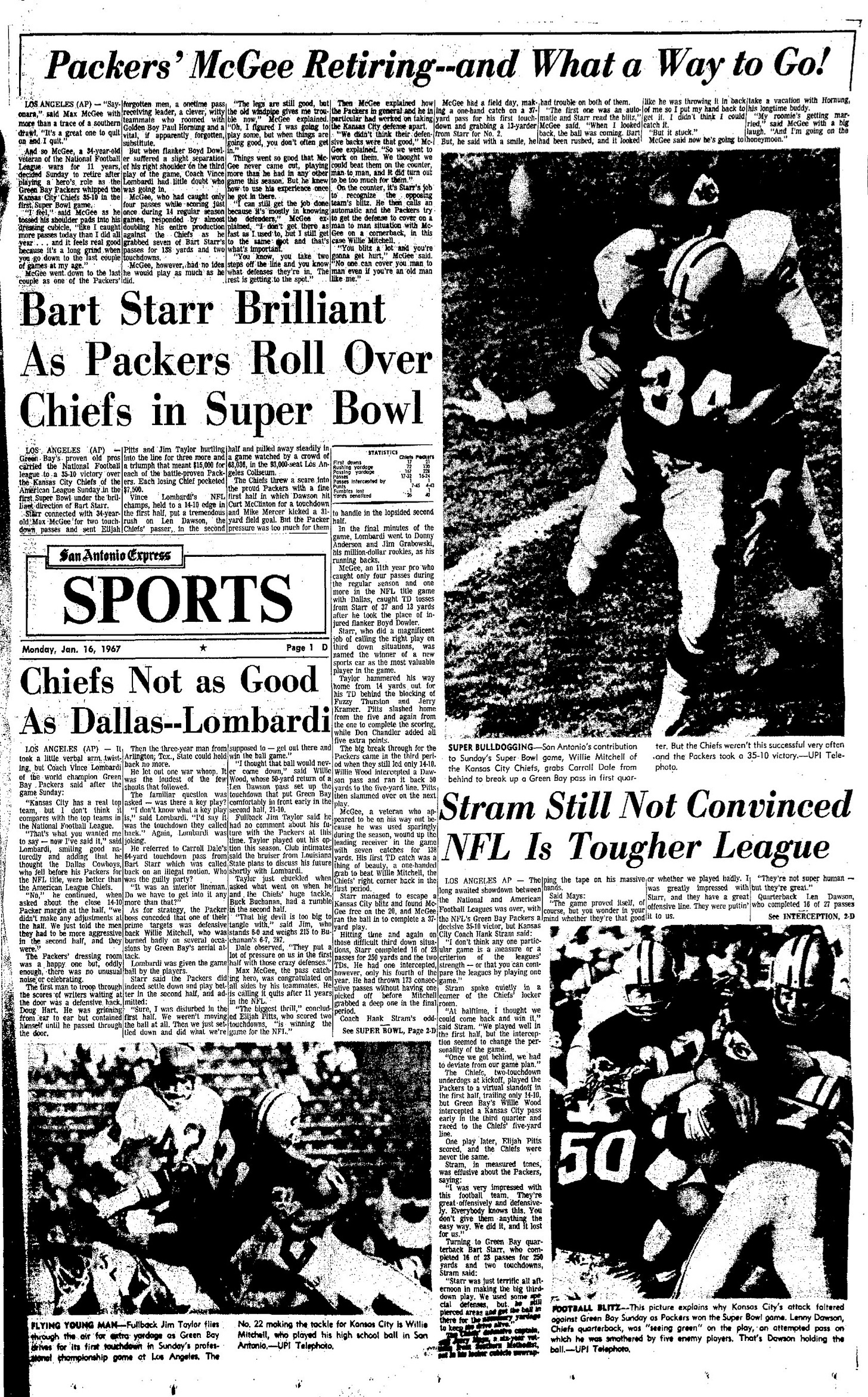

This started as a study in the historical research methods at Syracuse, taught by Lynn Flocke.2 I examined the coverage of Super Bowl I in eight newspapers — The New York Times; the Pittsburgh Press; The Post-Standard in Syracuse, N.Y.; the St. Petersburg Times in Florida; the Spokesman-Review (Spokane, Wash.); the Oakland Tribune; the San Antonio Express-News and The Washington Post.

I picked those eight for two reasons. One was convenience — I had access to them both through the Syracuse University library and the Binghamton public library, (where I lived at the time).3 The other was that I wanted to do newspapers in cities that both had NFL teams at the time (New York, Pittsburgh, Oakland, Washington) and didn’t (Syracuse, St. Petersburg, Spokane, San Antonio) to get a sense of how extensively the game was covered both in NFL markets and non-NFL cities.

What my research showed was extensive coverage of the game, leading up to and immediately after the game, in newspapers across the country. It was not an event that was ignored or that nobody cared about. From lead headlines to multiple stories, Super Bowl I was prominently covered in the newspapers of the time. In fact, there were numerous columns criticizing the hype surrounding the game – though curiously, they were all critical of television’s overhyping of the game and never mentioned the glut of newspaper coverage.

On the day of the game, the game was either the lead story or had a place of prominence on the sports cover of all eight newspapers. The day after the game, it was the top sports story in every paper, and even made its way onto the front page of several papers.

Newspapers from cities without pro football teams – in other words, ones without the kind of built-in interest as those cities with franchises – covered the game extensively. The St. Petersburg and San Antonio newspapers dedicated full-page treatment to the game.

The novelty of the game, and the merger of the two leagues, were no doubt the reasons behind this. This was not just any pro football game. It was the culmination of a seven-year battle between two leagues. The merger was the obvious storyline, and this was reflected in the newspaper coverage. The dominant theme was that the two teams represented the leagues themselves. This was not a showdown between the Packers and the Chiefs. This was a showdown between the NFL and the AFL, and the teams were mere representatives.

Leading up to the game, the storylines were whether or not Green Bay could maintain the NFL’s aura of invincibility, and how the Chiefs were carrying the hopes and dreams of the entire AFL. The coverage reflected little about the actual teams and more about the leagues themselves. Once Green Bay won in convincing fashion, the story was simple – the Packers had asserted the NFL’s dominance.

One interesting note was how prevalent the notion of money was in the coverage. The plethora of columns about the dueling telecasts revolved around the fact that this was a commercial, money-making enterprise for the networks. Also, it was noteworthy that virtually every story mentioned that the winners’ share was $15,0004 a player – something rarely mentioned in modern coverage of the sporting events.

Reporters routines for Super Bowl I

More than 1,000 media credentials were issued for the first Super Bowl, including 338 for newspaper reporters.

In 1967, pro football was in a rare space in the sports landscape. In some ways, it was considered the most popular sport in the United States. But this was a brand new event — not a long-established one like the World Series, the Kentucky Derby or the other major events on the sporting calendar.

Rozelle – a former public relations executive – gave his PR staff $250,0005 to spend on the media. “I don’t care how you spend it,” he told one of his staffers. “But when the news media leaves, I want them to be talking about all the things we did that they don’t do at the World Series.”

The reporters descended on Los Angeles in the week leading up to the game. With more than 1,000 credentialed media there, players dealt with far more reporters than they used to.

The interactions between media and teams was informal and relaxed. Rather than having formalized press conferences or availability sessions, reporters went to the team hotel to have meals with players or to visit them in their hotel rooms. Vince Lombardi conducted interviews in a small conference room at the team’s hotel in Santa Barbara – the coach didn’t need a microphone to be heard by the 30 or so reporters there. The Kansas City Chiefs stayed in Long Beach, where Fred “The Hammer” Williams entertained reporters with boastful predictions and demonstrations of karate moves right in the lobby of the team’s hotel.

The coverage of the game reflected sports journalism’s practices of the time. Game stories were primarily play-by-play descriptions rather than analysis. Stories tended to reflect one team’s point of view rather than have both teams represented. The coverage in The Washington Post (home paper for the NFL’s Redskins) was decidedly slanted in favor of the Packers. Coverage in the Oakland Tribune (home paper for the AFL’s Raiders) had a pro-Chiefs’ slant to it.6

What’s interesting is that for all the informal access reporters had — the kind of access modern sports journalists can only dream of — the coverage didn’t reflect it. Many of the stories only had quotes from one or two players, and they were used rarely. Many of the pieces felt formal, as if the writers were keeping a distance – which is at odds with the relaxed nature of the player-reporter relationship. This is indicative of the evolution sports journalism was broadly undergoing at the time. Although sports journalists were becoming more independent from the teams, there was still a sense of boosterism in some of the coverage.

To wrap up

It’s funny to think how embedded the idea of origin stories are into our society that the Super Bowl - the biggest event in our cultural calendar, the freaking Super Bowl - holds on the notion that it came from humble beginnings.

Truth is, from the beginning, the Super Bowl was considered one of the most important sporting events in the United States. The coverage of the game from an NFL vs. AFL perspective set the tone not just for the next few Super Bowls but one that continues today, when the AFC is pitted against the NFC. And the amount of coverage the game received at the time debunks the origin story that the first Super Bowl was not a big deal at the time.

Years later, Miami Herald columnist Edwin Pope remembered: “Even though the game wasn’t sold out, it wasn’t played in privacy like some people like to say. I will say an awful lot of writers missed that first one and never missed another.”

I’d say I’m like most people in that, given a rematch between the Chiefs and the Eagles, I’d be rooting for a meteor to hit the stadium. But, uh, maybe not?

Fun fact: I was taking this class and working on this project when my daughter was born.

There’s no way I was spending my grad-school stipend on a Newspapers.com subscription back then.

About $140,000 in today’s money.

The equivalent of about $2.4 million in today’s money.

Which is interesting, given the fierceness of the Chiefs-Raiders rivalry.

Seriously, outstanding. I wanted to read even more. Mostly, I want to know how/where the NFL PR people spent the money on reporters that Rozelle told them to do.

Excellent piece! Loved this -- everyone should read this before the Super Bowl. I also need to go back and watch some NFL Timeline shows! (Side note: Go Orange! Born in Utica, lived in Canastota as a kid before moving to Florida, but I still have family in Endicott and Binghamton! Glad to hear you were from there!)