The myth of the Super Bowl's origin story

People cared about the first game a lot. Like, a lot a lot.

Brian’s note: Most of this newsletter appeared on the Sports Media Guy website four and five years ago. I’m bringing it back and updating it in a few places, because I still think it’s an incredibly interesting story to tell about the history of the Super Bowl and the media’s story around its origin.

Vince Lombardi stood in his makeshift office inside one of the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum’s locker rooms. He had just coached the Green Bay Packers to a 35-10 victory over the Kansas City Chiefs in the first AFL-NFL World Championship Game, a contest the media had dubbed the “Super Bowl.”

A throng of newspaper reporters with their notepads, TV and radio broadcasters with their lights, cameras and microphones crowded into the room to interview Lombardi, who was holding the game ball his players had presented to him after the victory. The questions started coming about how good the Chiefs – the champions of the upstart American Football League – compared with the other teams in the established National Football League, the league the Packers represented

“Kansas City is a good football team,” Lombardi said, “But their team doesn’t compare with the top National Football League teams. I think Dallas is a better football team.” There was silence in the office, except for the reporters’ scribbling. Lombardi added, “that’s what you’ve wanted me to say, now I’ve said it.”

Lombardi’s quote about the Chiefs would be featured on the front pages of sport sections across the country, in some instances in headlines. In a game that was hyped as the meeting between two teams and two leagues, Lombardi’s proclamation was taken as the final judgment.

The Super Bowl has become, by any measure, not just the biggest sporting event in the United States but also a touchstone event in the country’s pop culture calendar. Super Bowl LVII will be one of the most watched TV shows in broadcast history, and thousands of media credentials have been issued for the game.

One interesting part of the Super Bowl’s mythology is its growth into a dominant sporting event from humble, modest origins. The first game was officially called the AFL-NFL World Championship Game – the name Super Bowl didn’t officially get tagged to the game until the third one. The Packers-Chiefs game was the only Super Bowl that did not sell out.

Reporters looking back at the game years ago recalled a lack of hype. Will McDonough, the longtime football reporter for the Boston Globe, remembered that “They issued just 328 media credentials then. (In 1991) it’s over 2,000 and they turned away 1,000.” Jerry Greene of The Detroit News remembered more bluntly, “There was no hoopla.”

The Super Bowl mythology is best encapsulated by Pat Summerall, the former New York Giants kicker and longtime football broadcaster: “There was none of the hype that we now associate with the game; in fact, nobody really wanted to play the game.”

In fact, the game story was on the front page of The New York Times the day after. Not the sports section. But the front page The Times. 1-A, above the fold. A photo of Lombardi accepting the trophy from commissioner Pete Rozell was the lead photo of that day’s paper of record.

Origin stories fascinate me.

They’re often used not to tell listeners or readers how something started but rather build a mythology around the thing itself, or the founders of it. This is how you get the almost cliche of tech companies beginning in someone’s garage. One researcher told This American Life:

It's like, no one wants to hear the story of the rich, well-connected guys who meet up at the Marriott conference room to hatch a business plan. There's no romance in that.

One of my first research projects in graduate school examined the Super Bowl’s origin story. I wanted to know if that origin story of humble beginnings was true or not.

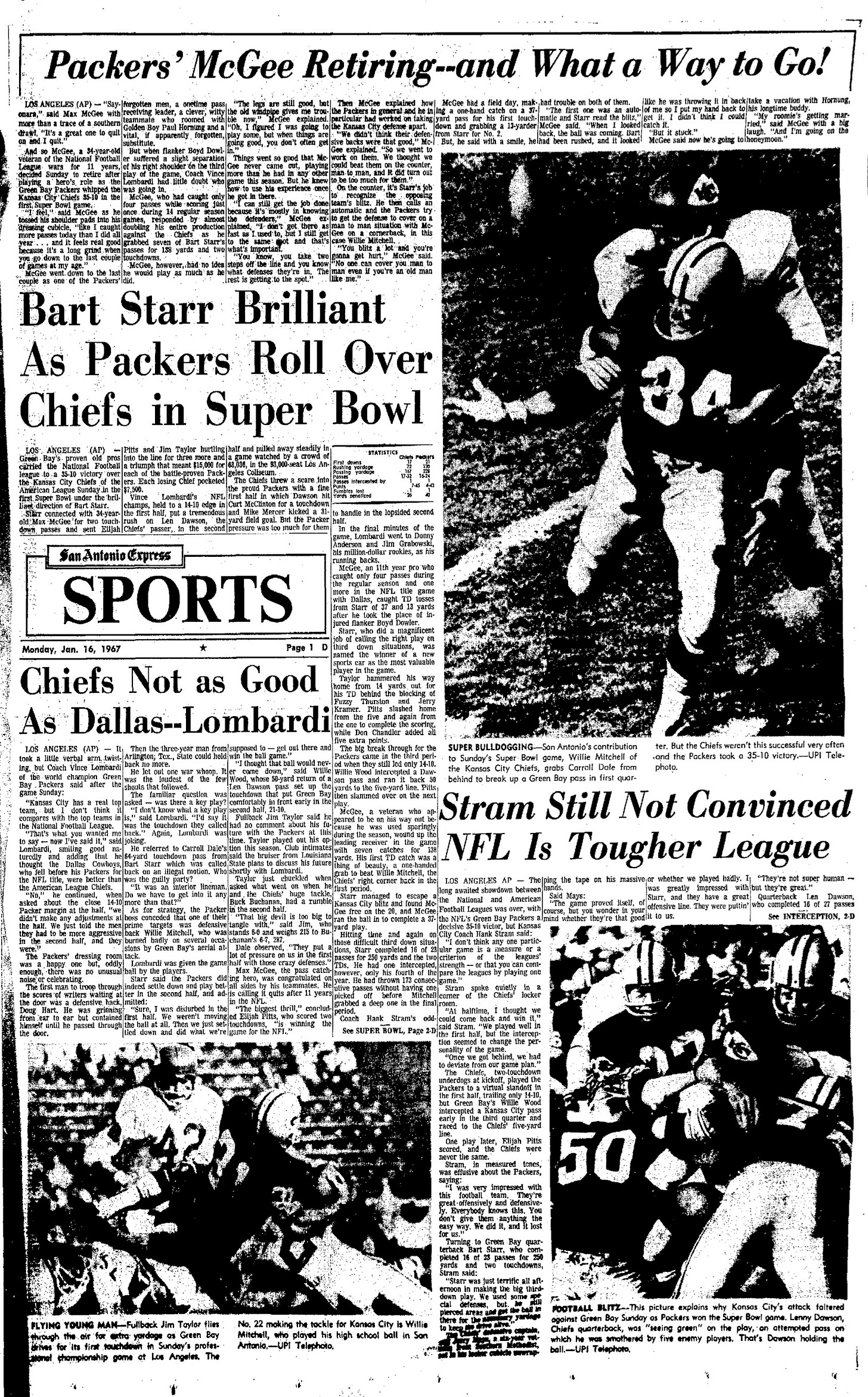

This was for a master’s level class in historical research methods. The study consisted of an examination of eight newspapers — The New York Times; the Pittsburgh Press; The Post-Standard in Syracuse, N.Y.; the St. Petersburg Times in Florida; the Spokesman-Review (Spokane, Wash.); the Oakland Tribune; the San Antonio Express-News and The Washington Post.

I picked those eight for two reasons. One was convenience — I had access to them both through the Syracuse University library and the Binghamton public library (where I lived at the time). The other was that I wanted to do newspapers in cities that both had NFL teams at the time (New York, Pittsburgh, Oakland, Washington) and didn’t (Syracuse, St. Petersburg, Spokane, San Antonio) to get a sense of how extensively the game was covered both in NFL markets and non-NFL cities.

What my research showed was extensive coverage of the game, leading up to and immediately after the game, in newspapers across the country. It was not an event that was ignored or that nobody cared about. From lead headlines to multiple stories, Super Bowl I was prominently covered in the newspapers of the time. In fact, there were numerous columns criticizing the hype surrounding the game – though curiously, they were all critical of television’s overhyping of the game and never mentioned the glut of newspaper coverage.

On the day of the game, the game was either the lead story or had a place of prominence on the sports cover of all eight newspapers. The day after the game, it was the top sports story in every paper, and even made its way onto the front page of several papers.

Newspapers from cities without pro football teams – in other words, ones without the kind of built-in interest as those cities with franchises – covered the game extensively. The St. Petersburg and San Antonio newspapers dedicated full-page treatment to the game.

The novelty of the game, and the merger of the two leagues, were no doubt the reasons behind this. This was not just any pro football game. It was the culmination of a seven-year battle between two leagues. The merger was the obvious storyline, and this was reflected in the newspaper coverage. The dominant theme was that the two teams represented the leagues themselves. This was not a showdown between the Packers and the Chiefs. This was a showdown between the NFL and the AFL, and the teams were mere representatives.

The coverage made the game about the leagues, and their respective reputations. Leading up to the game, it was a matter of whether or not Green Bay could maintain the NFL’s aura of invincibility or that the Chiefs were carrying the hopes and dreams of the entire AFL. The coverage reflected little about the actual teams and more about the leagues themselves. Once Green Bay won in convincing fashion, the story was simple – the Packers had asserted the NFL’s dominance.

One interesting note was how prevalent the notion of money was in the coverage. The plethora of columns about the dueling telecasts revolved around the fact that this was a commercial, money-making enterprise for the networks. Also, it was noteworthy that virtually every story mentioned that the winners’ share was $15,000 a player – something rarely mentioned in modern coverage of the sporting events.

From its start, the Super Bowl was considered one of the most important sporting events in the United States. The coverage of the game from an NFL vs. AFL perspective set the tone not just for the next few Super Bowls but one that continues today, when the AFC is pitted against the NFC. And the amount of coverage the game received at the time debunks the creation myth that the first Super Bowl was not a big deal at the time.

Years later, Miami Herald columnist Edwin Pope remembered: “Even though the game wasn’t sold out, it wasn’t played in privacy like some people like to say. I will say an awful lot of writers missed that first one and never missed another.”

Reporters routines for Super Bowl I

More than 1,000 media credentials were issued for the first Super Bowl, including 338 for newspaper reporters.

In 1967, pro football was in a rare space in the sports landscape. In some ways, it was considered the most popular sport in the United States. But this was a brand new event — not a long-established one like the World Series, the Kentucky Derby or the other major events on the sporting calendar.

NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle – a former public relations executive – gave his PR staff $250,000 to spend on the media. “I don’t care how you spend it,” he told one of his staffers. “But when the news media leaves, I want them to be talking about all the things we did that they don’t do at the World Series.”

The reporters descended on Los Angeles in the week leading up to the game. With more than 1,000 credentialed media members covering the game, players dealt with far more reporters than they used to.

The interactions between media and teams was informal and relaxed. Rather than having formalized press conferences or availability sessions, reporters went to the team hotel to have meals with players or to visit them in their hotel rooms. Vince Lombardi conducted interviews in a small conference room at the team’s hotel in Santa Barbara – the coach didn’t need a microphone to be heard by the 30 or so reporters there. The Kansas City Chiefs stayed in Long Beach, where Williams entertained reporters with boastful predictions and demonstrations of karate moves right in the lobby of the team’s hotel.

The coverage of the game reflected sports journalism’s practices of the time, in that the game stories were primarily play-by-play descriptions rather than analysis, and that stories tended to reflect one team’s point of view rather than have both teams represented. The coverage in The Washington Post (home paper for the NFL’s Redskins) was decidedly slanted in favor of the Packers. Coverage in the Oakland Tribune (home paper for the AFL’s Raiders) had a pro-Chiefs’ slant to it.

What’s noteworthy is that for all the access reporters had, for the way they met players and coaches for meals, at their hotel rooms and in informal interview sessions, that wasn’t reflected in the coverage. Many of the stories only had quotes from one or two players, and they were used rarely. Many of pieces felt formal, as if the writers were keeping a distance – which is at odds with the relaxed nature of the player-reporter relationship. This is indicative of the evolution sports journalism was broadly undergoing at the time. Although sports journalists were becoming more independent from the teams, there was still a sense of boosterism in some of the coverage.