Fandom, football, and Damar Hamlin

I’ve been planning a form of this essay for more than a month now.

As you’ll read in a few, some points Bomani Jones made on his podcast got me thinking about fandom and how sports communication research can help us make sense of how fans react to the world and to media coverage.

But my calculus changed a week ago, when Damar Hamlin collapsed.

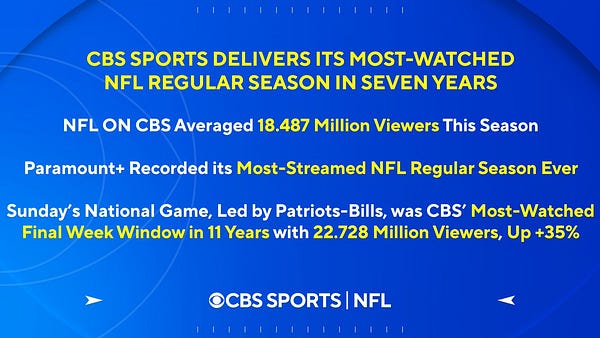

Late Tuesday morning, a little more than a week after a Hamlin’s s heart stopped during a football game and he nearly died on the field, CBS Sports’ PR tweeted the following:

I get it.

But man …

Multiple things can be true at the same time.

It’s beyond wonderful to see Damar Hamlin recovering so quickly so far. It’s a credit to the skilled human hands and minds of the Bills’ medical staff and the doctors at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center, to the science of the modern medical community, that Hamlin not only survived that night but is on the road to recovery.

It was inspiring to see the Bills’ reaction as an organization and as individuals — the leadership of coach Sean McDermott, the thoughtfulness and humanity of Josh Allen, the fierce loyalty of Stefon Diggs. It was maddening to see the NFL’s instinct to put The Game above this young man’s life, and it’s gross to see the same league using Hamlin’s story as a marketing tool.

It was awesome to watch Nyheim Hines’ touchdown return of the opening kickoff and to hear the call-and-response of the 71,000 fans at Highmark Stadium during “Shout.”

I really want the Bills to win the Super Bowl.

It feels like we’re all moving a little too fast.

In November, on his must-listen podcast, Bomani Jones was talking about the Minnesota Vikings and their fans:

People can’t just be satisfied that their team is good They need everybody else to say that their team is good … especially those of y’all that are from places that most people don’t wanna live in, you really want the respect from the rest of us.

Two days later, he came back to the point while chatting with Mina Kimes:

Why do you need respect from strangers about your football team?

There is a vast library of research into fandom, and sports fandom, that helps us understand how fans behave.

The concepts of BIRGing and CORFing — while admittedly sounding like a band that opened for Cannibal Corpse back in 1993 — are key in sports fandom research.

Researchers Daniel Wann and Nyle Branscomb defined these terms in 1990. BIRGing is “basking in reflected glory” and occurs when people associate themselves with successful others. CORFing is the opposite, “cutting off reflected failure,” or when people distance themselves from unsuccessful others. Wann & Branscomb found that highly invested sports fans (die-hard fans) have high levels of BIRGing—a classic example of this is a fan saying “we won!” after his or her favorite team wins. They also found that die-hard sports fans highly identify with their team’s successes and failures, and that less-invested fans (fair-weather fans) have higher levels of CORFing when their team loses. These fans are able to distance themselves from a team after a loss or bad game more than a die-hard fan.

In a 1991 study, Branscomb and Wann found:

High identification with a sports team may result in elevated levels of self-esteem, as well as increased frequency of feeling positive emotions. Identification also appears to act as a buffer against feelings of depression,alienation,and other negative emotions.

Underpinning this is social-identity theory. At the risk of oversimplifying a complex concept, the basic thought here is that all of us create our own identities that are connected to the groups we are a part of. It was coined by Henri Tafjel and John Turner in 1979. Beth Jacobson wrote that for Tafjel and Turner,

identity is also a function of the value and emotional attachment placed on a particular group membership.

Fandom is more than rooting for a team. It’s more than just wins and losses — Wann and Branscomb found that a team’s record does not impact the strength of fandom. Fandom is, at its heart, a community. At its best, it’s welcoming and open. At its worst, it’s cliquish and exclusionary.

Being a fan is awesome. To be passionate about something you love — the Bills, Beetlejuice The Musical, the Dave Matthews Band, Rainbow Rowell books, the MCU — is just the best. The connection to the material, the connection with other people, makes the world a better place. That’s why sports and art were so awkward during the pandemic, because without the connections, we’re just watching dudes play a game or videos on a screen. To be with people — dozens in a movie theater, a thousand in a Broadway theater, tens of thousands at a sporting event — while sharing this thing you’re experiencing together is magic.

The more you care, the more a part of your own identity that team (or show or whatever) becomes.

So, why do Vikings fans get so mad when their 13-4 team is dismissed as not very good? Why do Bills fans get so mad when anyone insinuates anything bad about Josh Allen?

It’s because being a die-fan of a team is a core part of how that person identifies. That connection is real. To say something bad about the team is to say something bad about them as people.

That’s what social-identity theory can teach us about fandom.

It’s about way more than just the game.

In the minutes after Hamlin's injury, I took off the Stefon Diggs jersey I've worn for almost every Bills game this season. It felt wrong to have it on at that moment.

I spent the next few days telling people I wasn't sure if I could watch football again.

I did watch football.

I watched most of the Bills-Patriots game from my New York City hotel room on Sunday. On Monday night, I had the Georgia-TCU game on, but I watched it the way I watch a show on Netflix.

I'm surprised how normal it felt. Except when any player got injured. Every time that happened, I felt a pit in my stomach.

But as I think about my own fandom in the context of the Hamlin injury and the research I brought up earlier, the conflicts become more stark.

Because deciding not to watch football, not to watch the Bills, isn't just a choice in how I spend my time. It goes against nearly 40 years of fandom and life. It goes against what I've always done for a living and what I've always wanted to do. It goes against my connection to home, my connection to friends and family, the new traditions my wife and I have started to the memory of my mom calling me at the end of every game until the year she died and opening with "How 'bout them Bills?"

Those feelings and connections are real. They matter. That's what the research tells us. That’s what our own experience tells us.

On the other side, there's the fact that a 24-year-old nearly died on the field so that I could have those feelings and connections.

The fact that it was apparently a random, horrific fluke (and not the result of a dirty play), and Hamlin's stunning recovery, has seemingly given us all permission to move on. And that makes sense. It's OK to like football, to watch it, to care about it. In life, we move forward. Time and tide stops for no man, and all of that.

But I'm afraid we're moving forward a bit too fast. I'm afraid Hamlin's going to be used as a prop, a character in an inspirational story the league and sports media tell about a sport. I'm afraid that this is going to become a "Win it for Damar" story — which, to the Bills' credit, they have not yet done themselves. I’m afraid that the apparent randomness of Hamlin’s injury (for lack of a better word) will obscure the inherent violence in the sport and the necessary efforts to improve player safety.

I'm afraid we're going to put the fear, the terror, the emotion we all felt last Monday into a box, to be used when we need "perspective" but otherwise forgotten as the business of the NFL moves on.

I get moving forward. I am moving forward. We all are. Most importantly, Damar Hamlin is moving forward and that is truly miraculous.

But a young man almost died playing football.

Moving on without a proper pause writ large, without reflecting on the situation behind throwing up three fingers, a heart emoji and a hashtag, just doesn't feel right to me.

The Other 51

On a special episode of my podcast recorded early last Thursday morning, Tyler Dunne tells us all about Damar Hamlin, what it was like to be in Cincinnati that night, and about watching and covering football going forward.